Can Humans Get to Mars Without Going Insane?

Clip: Season 25 Episode 16 | 12m 32sVideo has Closed Captions

How can future astronauts best prepare themselves to face these challenges?

Humanity's first Martian explorers will face extreme confinement, isolation and disruption of all bodily rhythms. The psychological stress from all of this could lead to a breakdown of social order among those on the mission – even mutiny. Are there lessons that can be learned about this from terrestrial explorers of the past?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Can Humans Get to Mars Without Going Insane?

Clip: Season 25 Episode 16 | 12m 32sVideo has Closed Captions

Humanity's first Martian explorers will face extreme confinement, isolation and disruption of all bodily rhythms. The psychological stress from all of this could lead to a breakdown of social order among those on the mission – even mutiny. Are there lessons that can be learned about this from terrestrial explorers of the past?

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(soft music) - Humanity's first Martian explorers will face one of the most extreme psychological challenges any human traveler has ever endured.

This small group will spend around six months in a spaceship the size of an RV just to get to Mars.

After touchdown, they'll move into a small habitat with little privacy and no real-time contact with people on Earth.

All they will have, in the midst of a cold, deadly void, is each other.

That's better than being alone, but the crew will eventually come up against the kind of monotony that few people have ever known.

Splitting up or turning back won't be an option.

There will almost certainly be no way to survive the mission if they don't do it together.

Centuries of history, along with modern research, suggest that this level of extreme confinement is not gonna be easy.

It may even prove to be deadly.

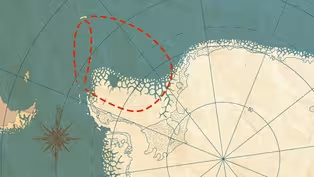

In the 17th century, one of the most enticing frontiers was the Arctic.

For hundreds of years, Western explorers looked for a so-called Northwest Passage, an elusive sea route through the icy waters that would connect Europe and Asia.

Many of the men who searched for it would succumb to the elements.

In June of 1611, the crew of a ship named Discovery was sailing through Hudson Bay, named for the captain of that ship, Henry Hudson.

They'd weathered a brutal winter, and it seemed they had survived the worst.

Except that, as they began the second year of this journey, nine of them were about to succumb to something even more treacherous than Arctic winter, human nature.

As Hudson steered their ship toward Asia, a mutiny broke out among the crew.

They forced Hudson, his son, and seven others onto a small boat and cast them off, never to be heard from again.

Four centuries later, we've conquered the Northwest Passage.

But as modern explorers turn their gaze to Mars, they face an age-old problem: how to account for humans' unpredictable response to stress and confinement as we undertake one of the greatest challenges our species has ever attempted.

Hudson's crew had been confined aboard their ship for over a year, and locked in the ice sheets of Hudson Bay for half that time.

They'd spent the long, dark winter cooped up in a smelly cabin, fighting frostbite, starvation, and despair as their supplies dwindled.

By late spring, fights broke out.

Finally, there was a complete social breakdown aboard the ship, leading to the fateful mutiny.

After casting Hudson and eight others off into the bay, the rest of Hudson's men seized the helm and sailed the ship back to England without him.

In many ways, it seems like today's explorers have it easier.

They have all kinds of high-tech vehicles and supplies to ease their way.

The first humans to go to Mars will know more about what awaits them than the sailors who set out to look for a Northwest Passage.

But they'll still be facing immense psychological pressure, the type that has done in many great explorers.

Henry Hudson wasn't the only one to deal with a full-on social breakdown among his crew during a long expedition.

In the summer of 1871, a sailor named Charles Francis Hall had a falling out with some of his crew en route to the North Pole.

One day, while waiting out the winter in the Arctic Circle, he drank a cup of coffee and died suddenly.

His last words were accusing his officers of poisoning him.

A decade later, an expedition led by Adolphus Washington Greely was on its own quest for the North Pole.

Two years into their journey, after failing to connect with a resupply ship, Greely's crew set up a camp on a small cape, waiting for rescue.

While they endured the unbroken darkness of Arctic winter in a windowless tent, despair and insanity broke out among some of the explorers.

Many fell sick and died.

One was executed for stealing food.

Only seven of the original 25 survived till their rescue.

As far as we've come in modern times, being cooped up with fellow explorers on long, harrowing journeys hasn't gotten any easier on our brains or our social relationships.

Back in the 1980s, one of the Soviet cosmonauts aboard the Mir space station reported that he spent nearly a third of his time in space in conflict with other cosmonauts.

And during the first crewed Apollo mission in 1968, the three astronauts fell sick and repeatedly fought with mission control.

They outright refused to wear their helmets during re-entry, fearing it would make their sinus problems worse.

It's clear why agencies interested in sending astronauts to space for long periods of time have started taking a direct look at these problems through simulations.

In 2010, researchers closed the hatch on a mock spaceship in Moscow with six men inside.

It was the beginning of 520 days alone together, with no sunlight or fresh air.

This simulation was called Mars500, a chance for scientists to figure out what kind of issues could come up in a spaceship or a hypothetical Martian habitat, and to see how well different people could withstand them.

The crew had a little excitement here and there.

They simulated a landing on Mars, put on spacesuits for a Marswalk, and navigated some simulated emergencies, like having their communication cut out for a week.

But for the most part, it was 520 days of the same four walls and the same six faces.

By the end, they all had increased levels of stress hormones, leading to depression, insomnia, disrupted sleep schedules.

And while there were no mutinies or arsenic-laced coffee, conflicts did break out among crew members and ground control.

In 2013, another simulation, called HI-SEAS, began testing how humans would react during several months together in a simulated Mars habitat in Hawaii.

- Well, the habitat itself was a dome shape, and it looks just like a Mars base, but the entrance door was just a normal door that you would see in any offices.

And it was just simply closing the door, but we, the crew, felt like we traveled from Earth to Mars.

- [Joe] The crew was all alone.

They couldn't step outside the habitat without a spacesuit.

And they had a 20-minute delay between communications with mission support, just as they would on Mars.

Sukjin was part of Mission VI, and he and his fellow crew members went through an intense period of selection and training.

- Anything that you experience outside in the daily life will be multiplied by 10, is what they say.

And it was kind of scary to me.

- [Joe] But after they walked through that door to the simulation, their mission got off to a strong start.

They cooked food together, they sang together.

They even made it through an unexpected loss of communication with ground control.

But then, less than one week into the mission, everything fell apart.

It started when one member was electrocuted while working on some equipment and had to be evacuated to a hospital.

- After that incident, another crew member became anxious about the mission and they decided to withdraw from the mission.

- [Joe] With two of the four members gone, the mission was discontinued.

- I was devastated by the fact that I had to stop the mission after all these preparations and after all these, like, goodbyes with people.

That type of an experience made me think that this is a really big challenge for us.

- These trials reflect what we've seen in real-life historical experiments, including Hudson's doomed expedition in 1611.

Tempers get short, interpersonal relationships break down, and sometimes, disaster ensues.

- I think one of the biggest challenges for survival is this interaction between the crew members.

There are other technical challenges, but I think the biggest challenge is how to resolve conflict and how to maintain the level of cooperation between the group.

- And there may never be a perfect solution to these challenges, because these reactions are rooted in our human nature.

The crews on many real and simulated expeditions suffer from monotony and sensory deprivation, which our brains just didn't evolve to endure.

Beyond just being boring, this kind of deprivation can decrease certain brain activity, and that's linked to negative psychological effects, like memory loss, trouble concentrating, and sluggishness.

The tight space with no escape puts crew members in a constant state of stress, even in people who aren't outwardly showing signs of psychological or behavioral disturbance.

All of these factors can contribute to cognitive decline, which can be a risky thing when operating complex equipment that stands between you and death in an extraterrestrial vacuum.

These are just some of the problems that come with sending humans on long, difficult journeys.

So, with all of this in mind, what do we do to help our chances of preventing a Martian mutiny?

These expeditions will be among humanity's greatest adventures, but they'll also be pretty boring and monotonous at times.

While we're trying to conquer outer space, the perils of inner space will be just as real.

Well, the first step is figuring out how to pick crew members who are most likely to be able to tolerate prolonged confinement with others.

Scientists are identifying personality traits and biomarkers that will help them predict who is most likely to hold up under pressure.

There's also growing recognition that astronauts won't be able to just tough it out.

Their psychological needs will have to be monitored and managed during their long journey.

That means finding ways to break up the monotony.

Some scientists are working on virtual reality and artificial intelligence devices as a way to help astronauts connect with people and places they've left behind, and keep a healthy state of mind.

But many hardships of confinement just won't be escapable.

So crews will also need to go through psychological training before they sail off into space.

Today, after vetting potential astronauts, NASA takes its future crews on geology field trips, along with psychologists.

Besides preparing for technical aspects of their job, they also learn non-technical skills, like teamwork and communication.

And before they head to the space station, they spend plenty of time running through simulated emergencies and practicing how to respond as a team.

These astronauts have the benefit of real-time support from the ground, but future Mars explorers won't be able to rely on live support from Earth.

They will need to form solid skills as a team before takeoff.

On a journey to Mars, there's no recourse if the crew can't get along, either with each other or with ground support.

If that happens, they could all find themselves like Henry Hudson, adrift in an inhospitable place without the things they need to survive.

It's one of the greatest challenges of our time.

Humans didn't evolve to endure these expeditions, but it's our human-ness that calls us to try anyway.

Uncharted Expeditions is a special series exploring the unique challenges facing human explorers.

As we set off on the next great era of discovery, beyond Earth.

Make sure you subscribe to PBS Terra, so that you don't miss a single episode.

And to learn more about the effects of isolation on astronauts in space, be sure to watch "Space: The Longest Goodbye" on the PBS app or just check the link down below.

Antarctica's Survival Guide for Mars Explorers

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 13m 41s | How did the extreme Antarctic winter affected the Belgica's crew? (13m 41s)

Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | NASA psychologists prepare astronauts for the extreme isolation of a Mars mission. (30s)

Watch Space: The Longest Goodbye with PBS Passport

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | Get early access with PBS Passport. (30s)

What an Antarctic Disaster Can Teach Us About Getting to Mars

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 15m 9s | How do you keep humans sane and relatively content in isolation? (15m 9s)

Extended Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 1m | The grueling journey to Mars. (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: